In the Goal and Scope (LCA Phase 1) phase of making a Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) you specify: what, why, how, and for whom your LCA is relevant. It’s a crucial phase in making LCAs, as it determines your outcome and how you interpret and check your results. That’s why you always return to this phase – throughout the later LCA Phases.

This article covers how to:

- Define the Goal

- Specify your scope and set system boundaries

- Choose the right LCA methodology

Image 1: The first Phase of an LCA defines its Goal and Scope.

Define your LCA’s Goal (why and for whom)

Why is this study conducted?

In the Goal definition, get clear on why you conduct the LCA, and how you intend to use the results. Do you, for example, want to know the environmental impacts of an existing product? Compare products*? Or use the LCA as a basis for design- or corporate decisions?

* In case you want to make public claims about the superior environmental performance of your product vs. a competing product (which would be called a “public comparative assertion”), special requirements for critical review apply – our specialists can tell you more.

For whom is this study conducted?

Likely, the section above already gives you a clue about your audience: is it product designers, decision makers inside or outside your organization, customers, or the public?

Consumers want to make sustainable choices, governments want to design good policies. Knowing your intended audience, and what insights are relevant for them, will help streamline your Impact Assessment (Phase 3) & Interpretation (Phase 4).

Moreover, it is great (though not mandatory) to state by whom the study is conducted, funded, and reviewed.

Define your LCA’s Scope (what and how)

The Scope gets more pragmatic: what is the product you assess, and how do you set up your study to achieve your Goal? For this, you define:

- Functional unit: what you’ll assess

- System boundaries: what you won’t assess

- Methodological choices: how to assess

Product & Functional Unit- Define what to assess

You want to assess the footprint of product x. Say a toaster. Ok, let’s go! Well… not so fast.

In LCA, you always define what you assess with a “Functional Unit”. This is any quantifiable unit in which you measure your product’s footprint. For example, a number of products, like 1 kg of eggs. Or a quantity attached to its function:

Imagine you have a toaster. First define its function: ‘toasting’. Now how do you measure this toasting? By defining a functional unit: for example ‘toasting 2 slices of bread’. If we want, we can further specify the functional unit, for example, by adding a timeframe (if this is what we want to know!). This would be: you could assess the footprint of ‘toasting 2 slices of bread in 1 minute – with your toaster’.

Comparing functional unit

If you compare your product’s footprint to another product, according to the functional unit – ensure they both comply with said functional unit!

- Going back to our toaster example. If you’re comparing three toasters for the functional unit “toasting 2 slices of bread”, you compare them on how much energy, materials, etc. they need to make 2 toasts. The one toaster might need less energy to produce the same amount of toast as another toaster.

Your data needs to be collected in accordance with your functional unit. For example, when your product unit is in kg mass, all your input data (i.e. raw materials, processes, packaging materials, etc.) has to be converted to the functional unit: kg mass.

Comparing functional units

If you compare your product’s footprint to another product, according to the functional unit – ensure they both comply with said functional unit!

- For example, if you’re comparing three toasters, you compare them on how much energy, materials, etc. they need to make ‘a’ toast within 1 minute. One toaster might need less energy to produce the same amount of toast as another toaster.

System boundaries – Define what not to assess

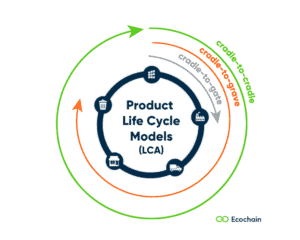

Setting healthy boundaries is key to keeping your cool, also in LCA. To decide which life cycle phases to include in your LCA, choose a “life cycle model”: e.g. Cradle-to-Gate, Cradle-to-Grave, Cradle-to-Cradle.

This determines which materials, transport, energy use, waste streams, and process emissions are part of our product system (and which are not). On those, you collect data in Phase 2 – learn how to do that here.

Methodology – Define how to assess

Like all scientific methods, LCA requires “methodological choices”. According to ISO 14040, you need to define allocation methods, the geographical & temporal scope, etc. But these are things Mobius and our specialists will guide you through.

Particularly, you’ll choose an LCIA method here – this might be prescribed by the LCA or reporting standard you follow.

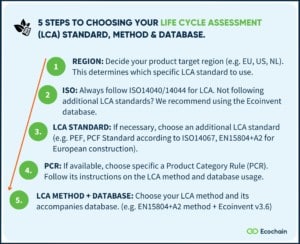

Image 3. How to choose an LCA standard, method & database.

How far do you want to go?

Also, in your Scope, you indicate how far you’re willing to go for good data. Data quality and the time/effort to collect data require balancing. Thus, think about how much primary data you already have, or are able to get from suppliers. For a screening LCA – to get a first impression – primary data is less relevant. You can set higher data quality requirements later!

Conclusion

Your Goal and Scope set the course of your whole LCA. BUT: LCA is an iterative process, and Goal and Scope might be readjusted in later LCA-Phases. For example due to better data availability or new insights.

Transitioning to the next LCA Phase (Inventory analysis) you’ll collect data. Read our data collection article here.